Ok so let’s remind ourselves of the point to PED use in climbing: maximising training results and enabling maximal opportunity for progression, all while avoiding weight gain via hypertrophy of large muscle groups, or excess retention of either subcutaneous or intramuscular fluid. Training, drug use, and climbing practice itself should synergistically work together to optimise strength to weight ratio while, obviously, not impacting overall health.

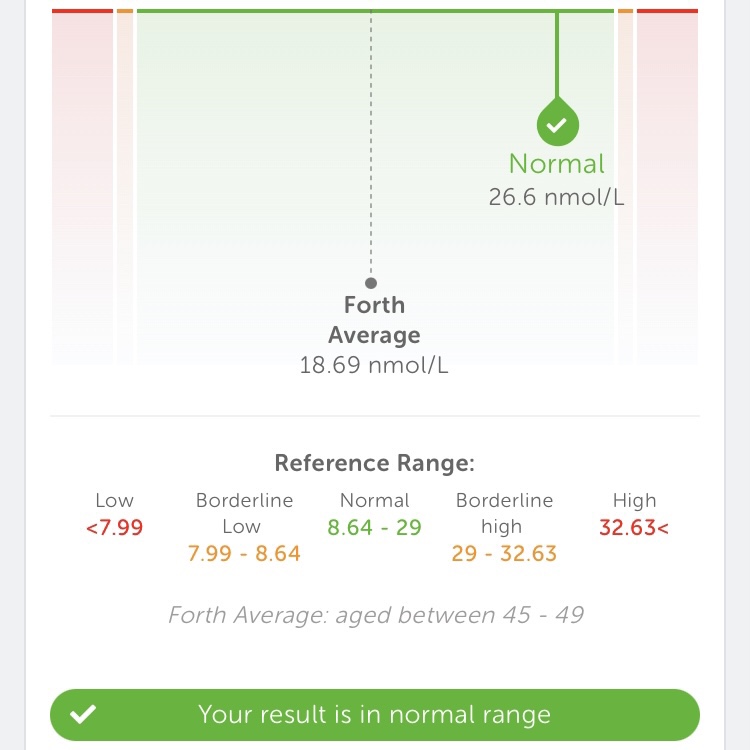

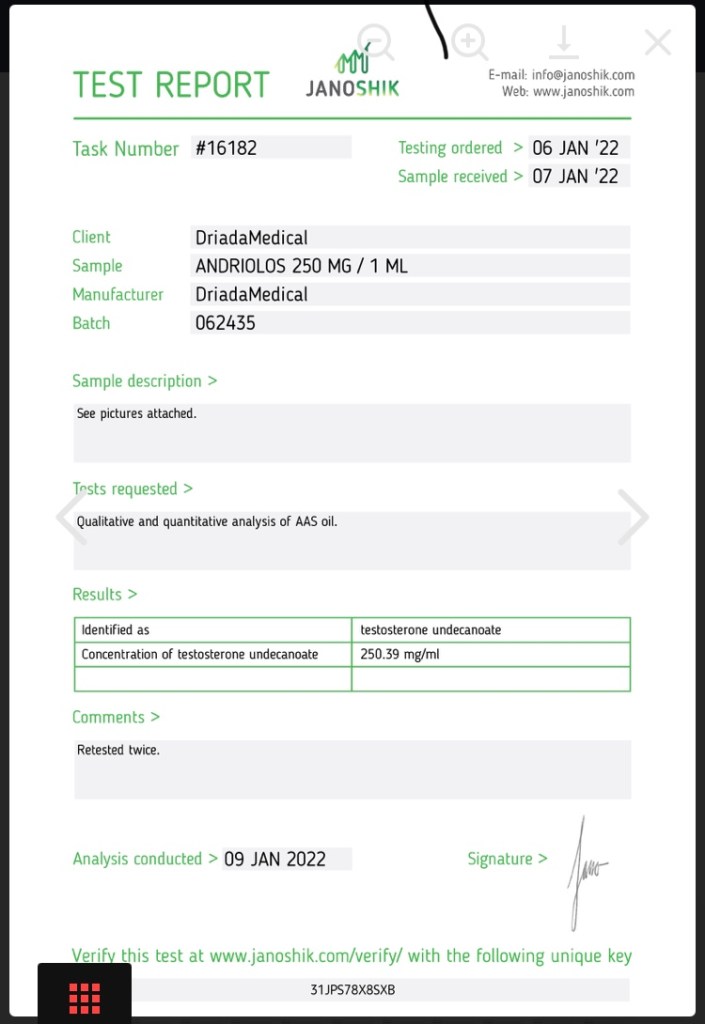

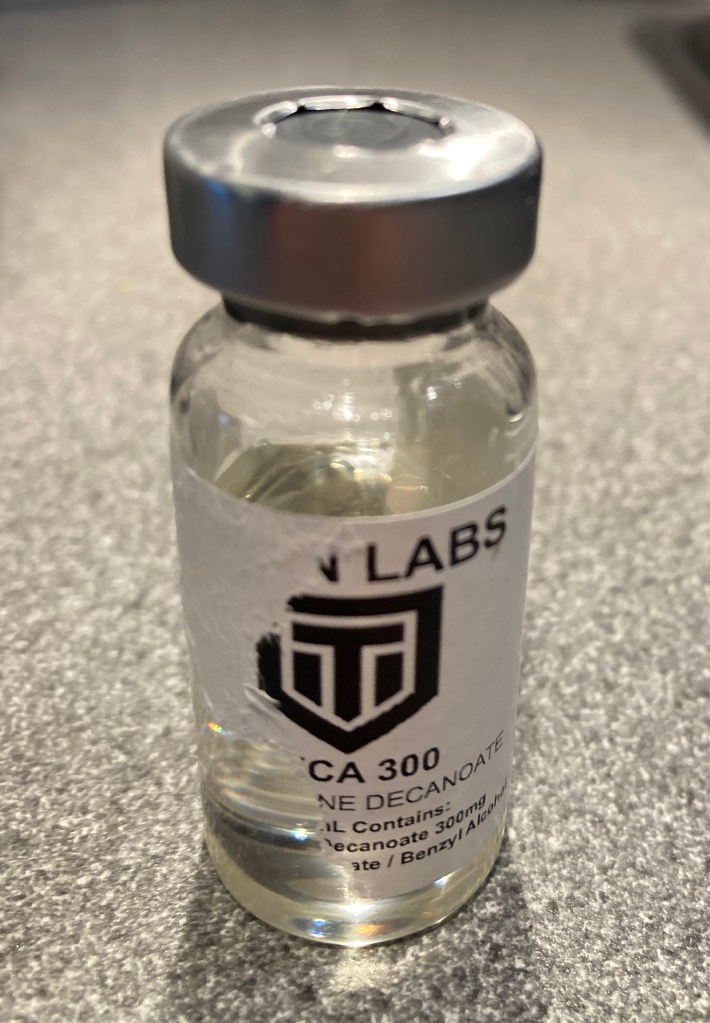

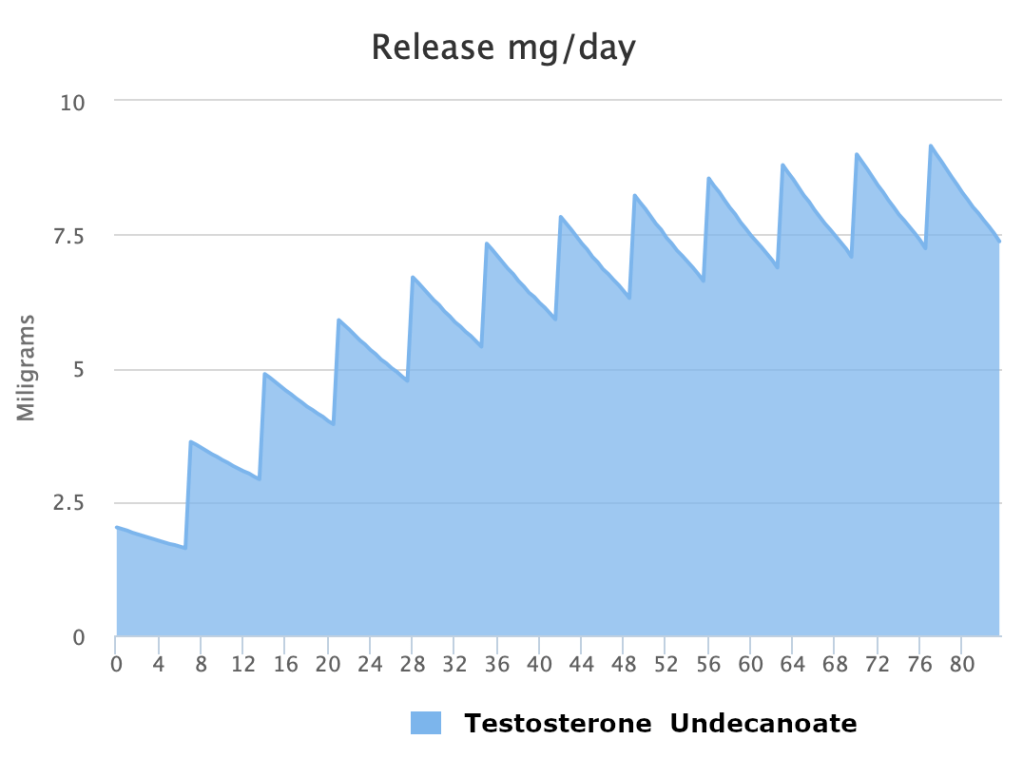

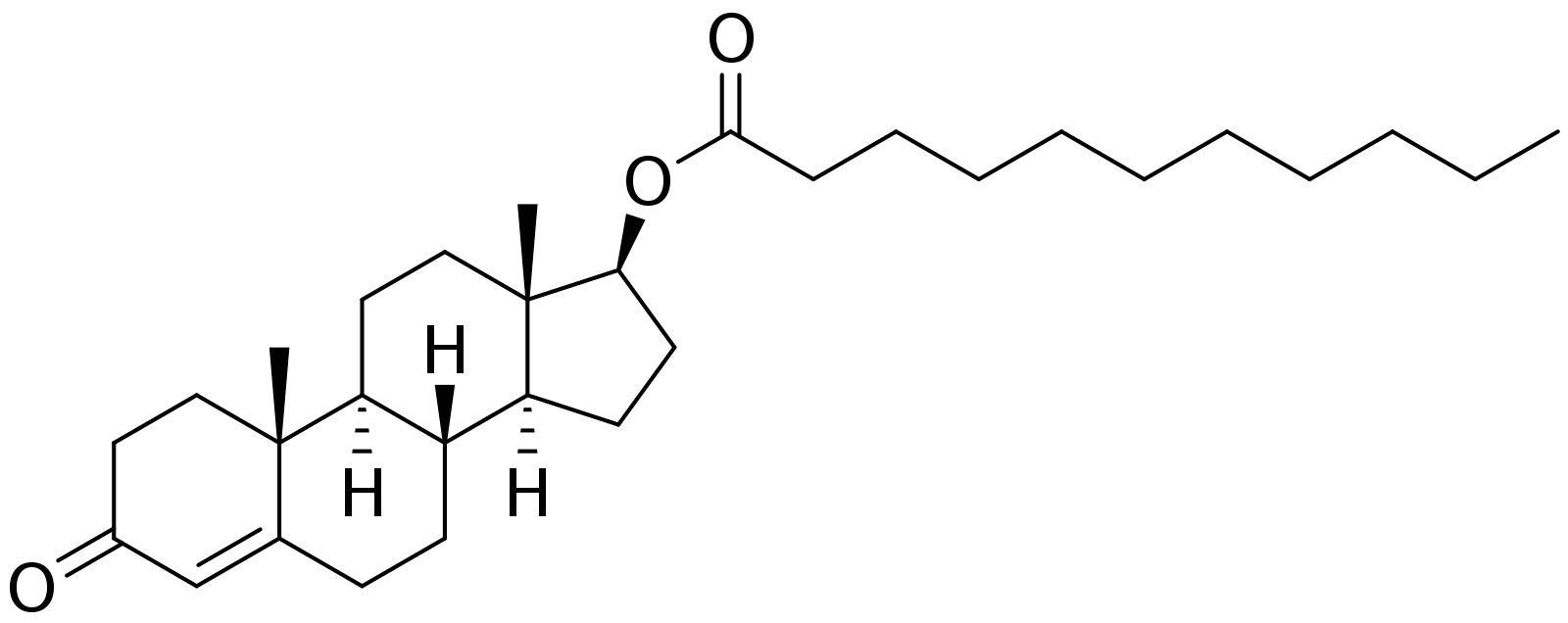

Hopefully I’ve already put myself in an optimal or at least enhanced hormonal environment in the day to day sense via my weekly administration of Testosterone and Nandrolone. There’s still some tweaking to do with this and it’s not something I can point to as leading to immediate benefits; it’s more likely I’ll be able to look back in a few years and see a clear delineation between pre and post PED use when it comes to my climbing progression. The injectable esters I’m using (nandrolone decanoate and testosterone undecanoate) are perfect for this long-term outlook, but is there anything I can do to help with specific, short term training objectives and performance goals which will be noticeable over the period of days and weeks, rather than months and years?

I’ve already discussed Anavar and Winstrol in a previous post and these are both 17α alkylated steroids, which is a term that probably needs explaining. The next two paragraphs are a bit technical. Please feel free to skip them if you don’t care about the science.

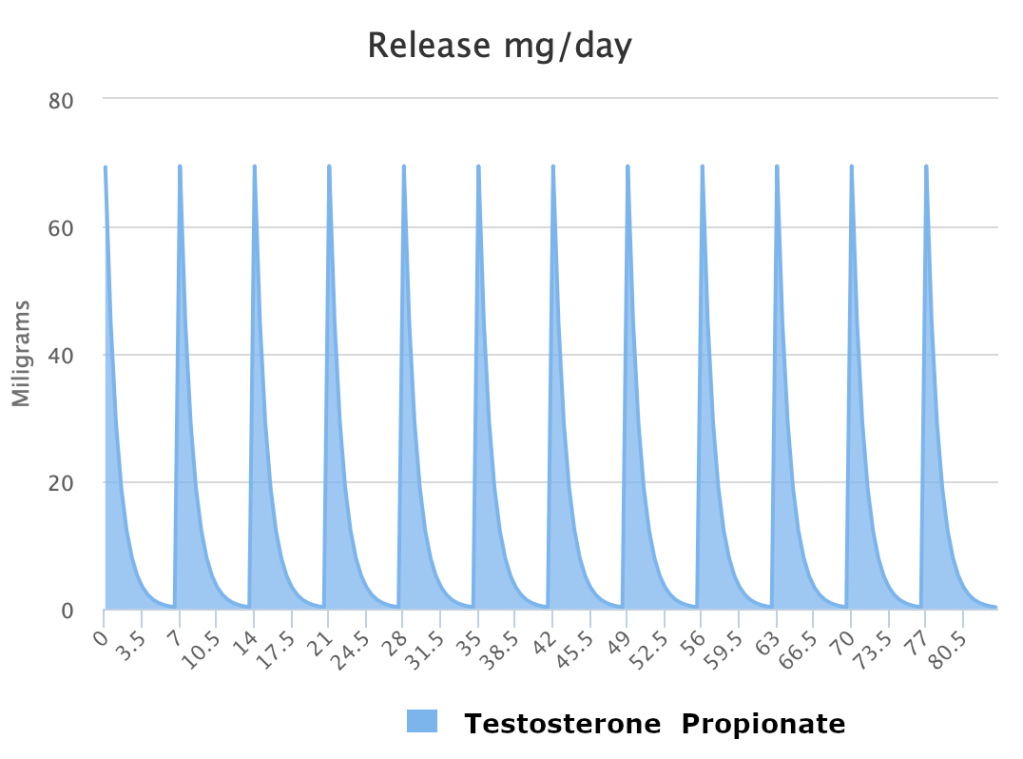

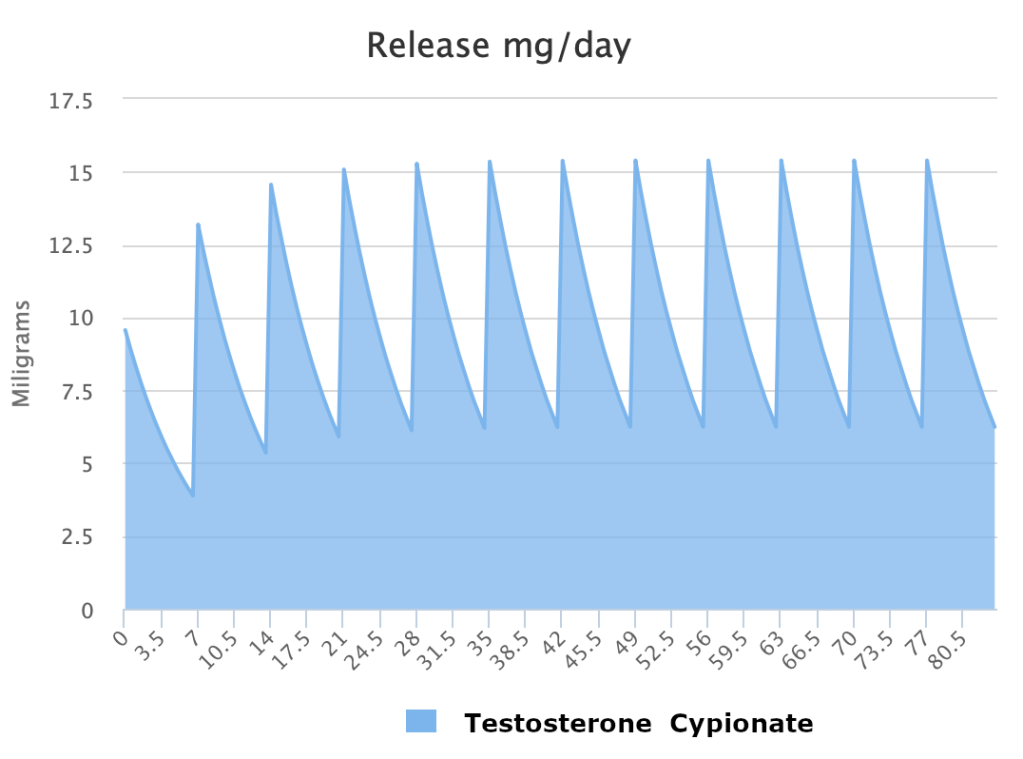

If you swallow testosterone, nandrolone, or masteron nothing will happen because the liver metabolises the molecule before it can exert any performance enhancing effect. So these compounds need to be injected intramuscularly and the addition of an ester group (decanoate, enanthate, etc), at the 17th carbon allows a larger dose to be administered less frequently where it will sit in the “injection depot” and dispense itself slowly over time. The longer the attached ester (or more specifically the higher it’s molecular weight), the slower the release rate and this is something we’ve already been through in some detail in a previous post.

An alternative way to fiddle with a given steroid molecule is to add a methyl or ethyl group to the 17 position instead of attaching an ester there. This makes it harder for the liver to break the drug down and you end up with an orally active compound with a serum half life, usually, of about 9 hours. However, unlike esterified steroids, 17α alkylated compounds have different characteristics from their parent molecule. For instance Superdrol is 17α methylated version of Masteron and the two have very different effects indeed. Contrast this to testosterone undecanoate and testosterone enanthate which have essentially the same effect, just with different pharmokinetics.

Welcome back those who skipped the chemistry. Where were we?

There is a downside to using these orally active steroids. It’s not particularly healthy to feed the liver something that’s intentionally designed to be difficult to metabolise. Thus 17α alkylated steroids can cause stress approximately equivalent to getting drunk, and as most climbers have realised by the time they get to be serious about the sport, chronic alcohol abuse isn’t particularly conducive to living clean, staying light, and all the other lifestyle choices which make us better at what we do. I’m sure that many of us are happy to spend the occasional weekend on the piss, but very few of us will be seen in the pub 5 nights out of 7 downing pints and knocking back shots. It’s the same with 17α alkylated steroids. They can be used for short periods without much concern but they’re not suitable for year-round, long term use.

There are essentially two reasons why I’d pop a pill to help with a short-term performance objective. The first is probably the easier to get across: let’s call it acute activity. Say I’m going out, conditions are good, and I’m planning to finally finish a project I’ve been working on for a couple of sessions. A drug which gives me immediate gains in strength and mental drive might lend the edge necessary to stick that hard, scary crux move at the top of the boulder. And if it acutely boosts work capacity, it will allow me more attempts during the session, therefore maximising my chances of sending. It doesn’t really matter if this drug is at the higher end of the hepatotoxicity spectrum because I’m only likely to use it once or twice a month.

The other reason why I might want to pop a pre-workout pill is to take advantage of progressive strength gains over a number of weeks: let’s call this chronic activity. In this case I may want to select a drug which builds in effect over repeated doses, rather than one which delivers an immediate and extreme boost in performance up front. This strategy would be useful if I wanted to work on a specific, defined weakness; say I want to improve my left hand half-crimp for a certain boulder I’m working on. In this scenario I might train the position every day for a few weeks before going back and trying the project again, and the drugs might increase the gain in crimp-strength I’m able to achieve in a given timeframe. I’d want these drugs to be at the lower end of the hepatotoxicity spectrum because I’m taking them daily for a few weeks.

Ok. So we’re splitting orally active anabolic steroids into two categories, those to aid with training and those for performance-day use. How do we decide which drug is suitable for which application? The first task is to list all the 17α alkylated compounds available to me and then narrow it down by applying the criteria which I discussed in a previous post. That only really leaves me with four compounds: Anavar, Winstrol, Halotestin, and Superdrol. Out of the four I’m expecting Anavar and Winstrol to be more suitable for chronic assistance over a weeks-long training block, and Halotestin and Superdrol to be more suitable for acute use on a per-session basis. The only way to know for sure though is to test them, so I’m going to standardise as many variables as possible into a protocol I can use to compare each of them directly.

Here’s a pretty brief rundown of my plan for testing these compounds. I’ll go into more specific detail in the next post, in the interest of stopping this one from becoming too unwieldy.

Each compound will be assessed for a period of two weeks. If they don’t show their utility over this period they’re not suitable for my purposes (although they still may be a perfectly efficacious drug to use in other situations). Calorie intake will be kept consistent during the tests, between days and from test to test. I’ll leave at least three weeks between each test to allow time for the drugs to clear and for my body to recover.

Dosage will remain the same between compounds for sake of comparison although some are slightly more potent than others. 15mg per day seems like an effective compromise dose between all four compounds while hopefully avoiding muscle hypertrophy associated with taking the doses higher. In addition to keeping the dose relatively low, I’m hoping that the short two week cycles might be another factor helping to mitigate unwanted mass-gain.

The dose of 15mg isn’t exactly pulled out of my arse my the way. The study “A quantitative expression for nitrogen retention with anabolic steroids” compares intravenous doses of Anavar and concludes that the mimimum effective dose is 2.5mg whereas no further nitrogen retention (their proxy for measuring anabolic effect), occurs after 30mg. Obviously I’m not planning on taking any of these compounds intravenously so let’s say that an oral dose, with it’s different pharmokinetics and bioavailability is half as active; this means that the dose range we’re looking at is 5-60mg with 5mg being minimally effective and 60mg blowing me up like a balloon. Say, (and this is the point I *am* pulling a figure out of my arse), I want to be a quarter of the way up that scale. That lands me at around 15mg. I’m sure a bodybuilder would scoff at that dose, but I’m specifically trying to avoid the gain in muscle mass which they seek.

So this is the protocol I’m going to use. I’m going to take the dose on an empty stomach two hours before I begin the workout. Then one hour before the workout I’m going to take a standardised portion of carbs (porridge, flapjack, something like that). I’m going to start with a standardised warmup/strength and conditioning session lasting one hour, followed by the the testing protocol which will also an hour in length. The purpose of the testing protocol is to assess the maximum one-arm half crimp for each side followed by how many pull-ups in total I can do over 5 sets.

I’ll graph total number of pull-ups achieved each day and the maximum half crimp weight for each hand as a percentage of a baseline measurement taken on the day before the test begins. I’ll also record my daily weight in kg and water content (as a percentage of body weight, measured by the hand-to-foot bioelectrical impedance machine in my gym).

This is where I’m going to leave this post for now; on a bit of a cliff hanger (excuse the pun). My laptop is broken and I’m tired of typing on my phone. I’ll continue after I’ve tested the first compound which will probably be Anavar, and go into specific detail on methodology at that point. Now I’m heading out to climb.

EDIT 1/4/2022: a quick addendum… I started programming the test protocol and realised that I could seriously irritate a nagging elbow injury I’ve had for a few months by doing pull-ups every day. Because of this I’m changing the plan a bit. I’ll be testing my left hand half crimp strength only. While I do this I’ll use the opportunity to rehab my right arm on a larger edge; I won’t be recording this as it will be about recovery rather than strength and there’s not a useful metric I can think of to codify the improvement.

EDIT 21/4/2022: this project is now on hold until summer. The exact timing when spring and autumn bouldering seasons start in the UK is always a bit difficult to predict. When it dries out and gets warmer (but not too warm) I spend as much time as I can on rock, and training takes a back seat to actual climbing. This has been the case for a few weeks now. Obviously with a potentially short window when rock is in ideal condition and climbing is good, this isn’t a time when I’m willing to devote two weeks at a time to daily training in the gym. No doubt when it starts getting too hot to climb hard I’ll be raring to go again with this research (I’m particularly curious to try Halotestin). Until then if I dabble, I’ll report back with my thoughts and findings.